AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth is a model that explains how economies may industrialize and develop through sequential stages.’

Rostow’s model outlines how national economies progress through sequential stages of development, emphasizing industrialization, technological advancement, and rising productivity as societies transition from traditional structures to modern economic systems.

Understanding Rostow’s Model in Human Geography

Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth describe a linear pathway through which economies move toward higher levels of development. It is a modernization model, meaning it assumes all countries can follow a similar trajectory toward industrial and economic maturity. Human geographers study Rostow’s model to understand spatial patterns of development, industrial growth, and the differing economic positions of countries at various stages.

Historical Context and Theoretical Foundations

The model emerged during the Cold War as an alternative to Marxist theories of development. Rostow argued that economic progress depended on technological innovation, investment, and societal changes that support industrial growth. This perspective frames development as an internal process driven by economic modernization rather than external political structures.

Key Assumptions

Development is linear and sequential, with each stage preparing conditions for the next.

Industrialization is the engine of growth, enabling productivity and income expansion.

Traditional societies must transition toward openness to innovation, capital investment, and global trade.

All countries can eventually reach high levels of mass consumption, given the right conditions.

The Five Stages of Economic Growth

1. Traditional Society

This stage is characterized by subsistence-based economies reliant on primary-sector activities such as agriculture and mining. Productivity is low because of limited technology and skills. Social structures tend to be hierarchical, and economic mobility is restricted.

Primary-sector activity: Economic work focused on extracting natural resources, including farming, mining, and fishing.

Limited infrastructure and minimal investment reduce opportunities for industrial growth. Most people work in rural settings, and the economy depends heavily on environmental conditions.

2. Preconditions for Takeoff

In this stage, societies begin adopting new technologies, improving infrastructure, and encouraging education and entrepreneurship. A shift toward commercialization of agriculture often occurs, creating surplus production that can support investment in other sectors.

These early transformations create a climate favorable for industrialization. External influences, such as trade connections or foreign investment, may also help generate momentum.

3. Takeoff

The takeoff stage marks the beginning of rapid industrial growth. Manufacturing expands, investment increases, and productivity rises across key industries. Urbanization accelerates as workers move to industrial centers.

This photograph shows the dense built environment and industrial facilities of an urban manufacturing town. Such landscapes are typical of Rostow’s takeoff and drive to maturity stages, when factories and clustered housing reflect rapid industrialization and migration to cities. The image includes local details not required by the syllabus but provides contextual realism for an industrial cityscape. Source.

Industrialization: The process of developing large-scale manufacturing and technological systems that increase economic productivity.

During takeoff, economic growth becomes self-sustaining because rising profits and productivity encourage further capital investment. Political and institutional reforms may also emerge to support industrial expansion.

A normal sentence here ensures proper spacing between definition blocks.

4. Drive to Maturity

At this point, economies diversify technologically and industrially. New industries grow while older sectors modernize. Productivity increases across all economic sectors—primary, secondary, and tertiary—and the workforce becomes more skilled.

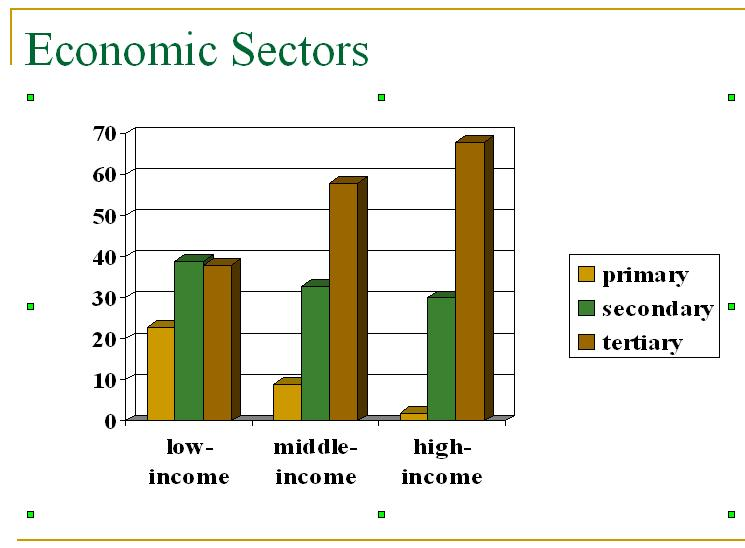

This graph links per capita income to the changing importance of primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, illustrating how economies diversify as they grow richer. It visually complements Rostow’s idea that countries move from agriculture-dominated structures to industrial and then service-oriented economies. The figure includes numerical details beyond the syllabus but reinforces the structural transition across stages. Source.

Internal and external trade networks expand significantly. Countries in this stage produce a wide range of goods and services, integrating more fully into the global economy. Infrastructure becomes highly developed, including transportation, energy, and communication systems.

5. Age of High Mass Consumption

The final stage features a shift toward consumer-oriented economies dominated by services and high-value goods.

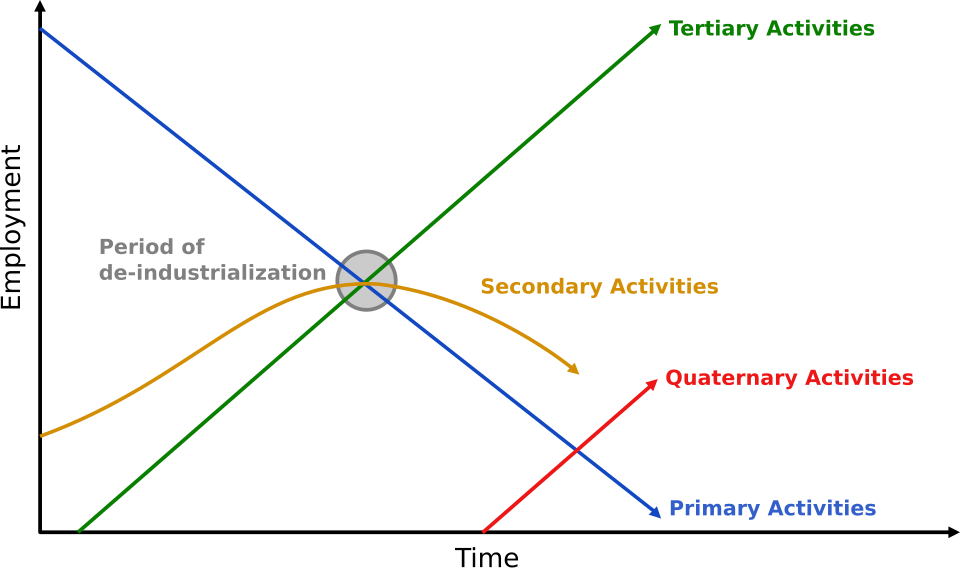

Clark’s sector model illustrates how the relative importance of agriculture, industry, and services changes as economies develop. The curve for primary activities falls over time, the secondary sector rises and levels off, and the tertiary sector grows in later stages. The diagram includes more sectoral detail than the syllabus requires but reinforces the concept of structural economic change. Source.

Tertiary-sector activity: Economic services such as retail, transportation, banking, education, and health care.

Societies in this stage tend to have strong social welfare systems, high levels of education, and widespread access to modern technology. Economic priorities move from industrial growth to quality of life and social well-being.

Strengths and Geographic Significance

Rostow’s model helps geographers understand broad patterns of development and industrialization. Its clear sequential structure makes it useful for comparing countries and analyzing global economic disparities. The model also highlights the importance of technological change, investment, and structural economic shifts.

Critiques from a Human Geography Perspective

Many geographers argue that development is not always linear and that historical, political, and cultural contexts shape economic outcomes. Critics also note that Rostow’s model reflects Western experiences, ignoring dependency relationships, colonial histories, and global economic inequalities that may limit development paths.

Additional Limitations

It assumes all countries have equal access to resources necessary for industrialization.

It minimizes the role of global trade structures that favor core economies.

It oversimplifies internal social and political complexities that affect development.

It overlooks environmental constraints associated with industrial growth.

Why Rostow’s Model Matters Today

Although simplified, Rostow’s framework remains influential in understanding industrial patterns, development trajectories, and global inequalities. It provides a foundation for analyzing why some economies industrialize quickly while others face structural obstacles. Human geographers use the model to evaluate spatial variations in development and to assess how industrial change shapes places and populations.

FAQ

Rostow’s model acknowledges that traditional societies may resist technological or organisational change, but it treats this resistance as a barrier that must eventually weaken for development to begin.

Resistance can slow or interrupt progress through the early stages, particularly the move from traditional society to the preconditions for takeoff, where new values, institutions, and education systems must become more widely accepted.

Takeoff requires a substantial rise in capital investment to build factories, transport networks, and power supplies.

According to Rostow, once investment consistently exceeds a certain share of national income, it creates momentum, allowing industrial growth to become self-sustaining and pushing the economy into later stages.

While the model presents development as linear, countries can experience setbacks.

Economic recession, political instability, or loss of investment can halt progress and cause features of earlier stages—such as reduced industrial output or weakened infrastructure—to reappear even after takeoff.

Trade can support different stages in distinct ways:

• During the preconditions for takeoff, trade opens markets for agricultural or resource-based exports.

• After takeoff, industrial exports generate revenue for reinvestment and diversification.

Sustained integration into global markets helps economies advance toward maturity and high mass consumption.

Government policy can accelerate structural change by supporting education, infrastructure, and industrial diversification.

Policies that encourage technological innovation, stable financial systems, and transparent institutions help maintain growth, allowing the economy to expand into new industries characteristic of the maturity stage.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one characteristic of Rostow’s takeoff stage in the model of economic growth.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for a clear explanation of a characteristic of the takeoff stage.

1 mark: Identifies a correct characteristic (e.g., rapid industrial growth).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation (e.g., increased investment in manufacturing leads to rising productivity).

3 marks: Shows clear understanding by linking the characteristic to wider development processes (e.g., industrial expansion drives urbanisation and self-sustaining economic growth).

(4–6 marks)

Using Rostow’s model, analyse how the transition from the preconditions for takeoff stage to the drive to maturity stage reflects broader changes in a country’s economic structure and development patterns.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for demonstrating understanding of the transition between stages and its implications for economic development.

1–2 marks: Basic description of either or both stages (preconditions for takeoff and drive to maturity).

3–4 marks: Clear explanation of changes between the stages, such as technological adoption, diversification of industry, and infrastructure development.

5–6 marks: Detailed analysis showing how structural shifts reflect broader development patterns (e.g., movement from primary to secondary/tertiary sectors, increased global integration, rising productivity, institutional change).